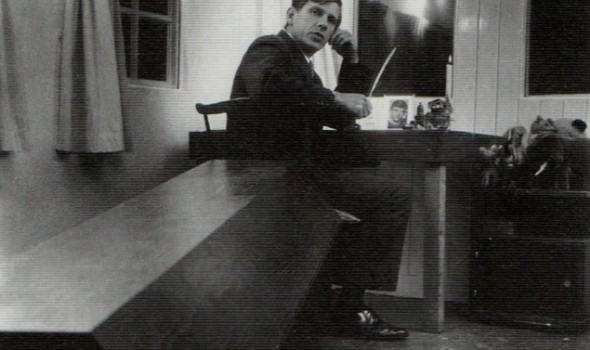

A circus boy

Hymn for M.

Oh Thou who knowest and understandest all,

Things Thy Son has no time for, nor patience,

To Thee, dear Mother, I sing this song:

Borne of Thee, I return to Thee.

May it not be long before I am one with Thee.

1 – Birth

First chapter

Wherein the writer contends that he was born uncommonly evil; wherein he attempts to explain his morbid outlook on earthly existence.

It is beyond doubt that I am evil.

(That man is completely evil, and may be said to be incapable of any good, is well established and, fortunately, it is not disputed, except by a few fanatics and lunatics. The question still remains whether man is partly or wholly guilty of his own wickedness. I believe that about half of man’s wickedness stems from nature and birth, while the other half is accounted for by his own free will and choice, which lead him on a path of death and destruction. If human existence were to have any validity and assurance of Eternal Salvation, such would exclusively be through God’s infinite and inscrutable mercy, which is the first, last and only hope of mortals. But this aside.)

If ever the circumstances under which a creature was born established how wicked it was and unworthy of living, it was the circumstances of my birth.

My birth transpired in an extremely labourious manner and lasted thirty-four hours of nigh uninterrupted contractions, which slowly strangled me, again and again, as the cruel prelude of Spanish executions in bygone times. I was born breathless and blue. It was towards the hour of six in the evening; complete darkness reigned outside, and a bitterly cold wind carried with it the first wet flakes of a rising and howling blizzard.

No men were present at my birth: the old, beardy doctor Montezinos, a caring and well-liked alcoholic who was never drunk, had gone away during one of the brief interruptions between contractions, to quickly consume some morsels of scrapple at the residence of a school friend of my parents who lived nearby. When he entered the delivery room again, he had trouble wresting my miserably cold little body from the hands of the midwife, who was slapping my chest and back. He tried to elicit a noise out of me but at first he had just as little luck as she. With improvised ingenuity, he kneaded my chest with his hairy claws, already bent by the onset of arthritis, permanently deforming it into the start of a sunken chest. But now, finally, I let out the requisite noise: first cooing, then squeaking, then screaming. I was born and, for better or for worse, breathing, and destined to live, and to die only much later.

’Blessed are those who scream,’ said the old doctor Montezinos, ’tis an essential virtue, we all depend upon it.’ He was intoxicated but never conclusively proved his drunkenness, and into the small room of the poverty-infested dwelling in Amsterdam, second floor, number 68, Van Hall Street, he belched the smell of recently consumed scrapple, of which microscopically small fragments stuck in his beard.

In addition to the midwife, Doctor Montezinos, the new mother and me, a neighbour was also present in the delivery room: this woman, who lived on the first floor and had been abandoned by her husband, a consumptive basket maker, lived off the small sums of money sent to her at highly irregular intervals by a mother or aunt from the province, and she knew the art of laying on hands, card reading and similar secrets that she, however, never applied for money or gain. She touched my clammy crown that had narrowly escaped Death, and muttered something like: ‘You see? Oh, wait, actually not.’ After discerning a slight unevenness, she had wrongly concluded that I had been born with a caul. ‘Much light shall shine upon him. Bright light. Many lamps. And everyone will look. A lot of people.’ She sighed and half fainted, as she was used to doing on such occasions.

The doctor had just taken himself off, filling the house and staircase with the lingering scent of his regurgitations, when disaster struck anew: my mother had no milk. They had misjudged her tensely swollen breasts, believing they were full of sustenance for a newborn. I refused to drink, which was puzzling. Were the nipples clogged? The midwife, already an expert in the art of infant-slapping, now began squeezing and pressing my mother’s breasts to no end. Full, they were indeed, but the liquid that abundantly gushed forth was not the requisite creamy-white juice of life, but a seeping, half-fermented fluid, which contained almost no nutrients.

In a months-long, unresolved battle between adult determination and childlike repulsion toward life, I was alternately fed buttermilk, watered-down cow milk, dissolved sugar, diluted carrot juice and warmed rice water, endlessly defiling bed linens, curtains, wallpaper, floor and furniture. The adults won the battle, and again I continued living, and acquired the resistance to withstand a multitude of childhood diseases.

I must have been sick almost constantly during the first years of my life, from what I have been told. Still very vaguely, and undetermined with respect to place and circumstances, I have retained these images in my memory: small spaces full of whispering under dim, subdued lamplight; the movements and accompanying little sounds of someone mixing and dissolving tablets, potions and powders; a figure that supports my head and tries to feed me something that is either too hot, too cold, too sweet or too bitter.

In later memories, the images become sharper; the voices are louder and I understand the words. Also, I know more or less by name what it is that I am supposed to drink or swallow. And I know that I am ill and that I will stay ill my entire life.

In one of these remembered images, I am sitting motionless on a chair inside the room, close to the window. Outside, a weak winter sun hangs low and languid over the ugly blue-gray roofs of ugly houses. I am three or four years old, and I am in pain, because I am sick. The pain, deep and throbbing, is just behind my ears, in both the hinges of my jaw, which is wrapped in a cloth, as if I were a dead body that has yet to enter a state of rigor mortis. If I breathe through my nose, the pain seems to spread forward from around my ears, and upward to just below my eye sockets. If I breathe through my mouth, the pain pushes deeper inward, filling almost the entire cavity of my mouth. I ceaselessly alternate these two modes of inhalation, lest the pain advance too far from its starting point, and, moreover, I move as little as possible, because moving creates a draught, and a draught creates coolness, and the slightest coolness on my face increases the pain.

Perhaps it was then that the overpowering and all-eclipsing realisation forever settled in me that to live and to act, or to live and not to act, is all equally pain, and fear, and dismay, and that it is disastrous and a great misfortune to be born and to live.

—

Continue: the Second chapter.

Many thanks to co-translators Jaason von Banniseht en Mireille Mazard

Sympathiek en interessant project om enkele hoofdstukken van Reve te vertalen.

Ik denk dat ‘evil’ voor ‘slecht’ niet het juiste woord is.

De eerste zin zou ik zo vertalen:

There can be no doubt that I am a bad person.

Groeten,

Hans van Leeuwen